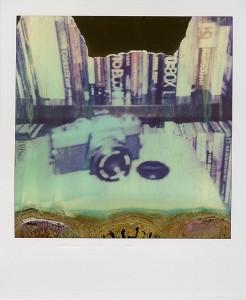

Polaroid Art

We have the Impossible Project to thank for the resurgence of Polaroid photography. Polaroid is a very tactile medium, from unsealing the silver paper wrapped carton to the comforting sound of the motor pulling the cartridge into the body of the camera when you close the door.

As you handle the camera depending on which model you have, it will likely feel ungainly in the hand, not having had the years of ergonomic engineering of a Nikon or Canon. Once you establish a steady grip on the camera, locate the shutter release button, and have mastered the lighter / darker button, you are ready to shoot.

If the Nikon is the precision drafting tool then the SX-70 or equivalent is the artist’s palette. So what makes the Polaroid image so enduring? And how do you create the works of art that can undoubtedly be sculptured from its arcane mix of plastic, metal and chemistry?

The first thing is to remember its square format. The rule of thirds don’t apply in a square format, and centreing your image generally does. Given the simple optics on a standard Polaroid camera, it’s not easy to get short depth of fields, so managing the background is important. Try to find simple uncluttered backgrounds.

There is a tendency for the Impossible Project film to vignette, so with this natural photographer’s aid built in to the output you can use this to hold in the edges.

Most Polaroid film needs a little extra light and shooting with the in-built flash helps get a good exposure and can add some modelling to the image. Beware getting too close as this will create a flat light. If you can light the subject area well, then I prefer not to use the flash. If you can, find textured backgrounds, the light drop-off characteristic of the film will add depth to the textures.

Monochrome films give a reasonable range of tones and with the chemical fading intrinsic to the film, your final print will always have an elegant analogue patina. To maximise this affect try to light the subject a little and keep the background dull, this will bring an extended light drop-off from subject to background and create a stronger three dimensional separation in your image.

The colour film provides that slightly washed out seventies appearance, which really accentuates the retro look we associate with Polaroid. So take advantage of this and bring into your shot a number of colours, they will not fight with each other, they will nicely fade into a subtle rainbow of tones that will enhance the charm of the shot.

Your final output which comes perfectly surrounded within a neat and uniquely identifiable rectangular frame, will potentially be a work of art. Certainly, many photographers and exponents of post-processing can spend hours trying to get the retro, old master, faded, seventies look, that can with care and practice drop straight out of your Polaroid camera.

They may cost a couple of pounds each, however it will cost a lot more in time to ‘create’ one of these with your precision state of the art brand cameras and Photoshop.